An Urdu Dove, AI, and Me: Reading Tarar's Untranslated "Fakhta" in Italian

Mustansar Hussain Tarar, a true giant of Urdu literature

A little over a year ago, on March 25, 2024, I had the privilege of sharing here on Learn Vedanta Substack the excitement of a podcast interview (and accompanying article) with Mustansar Hussain Tarar, a true giant of Urdu literature whose work had deeply struck me. Our conversation revolved around his masterpiece "Bahaao" ("The Sorrows of Sarasvati"), a profound and visionary immersion into the Indus Valley Civilization.

Despite his stature as a master, with a vast body of work spanning novels, short stories, and unparalleled travelogues, the frustrating reality is that only a tiny fraction of his work has been translated into English or other languages, remaining inaccessible to an international audience. A genuine loss, given the universal richness of his pen.

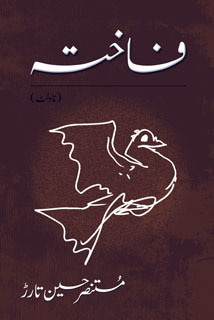

Fate, however, sometimes weaves unexpected threads. I stayed in touch with his son, Sumair Tarar, a multifaceted artist, a person of exquisite kindness and helpfulness. Driven by an irrepressible desire to delve further into Tarar's literary universe, over a month ago, I confided in him my curiosity about one of his early works, the novelette "Fakhta" (Dove), first published way back in 1957. An almost mythical text, which proved impossible to find in any translation. With generosity, Sumair provided me with a scan of the original Urdu book.

The AI Help

This is where the spark of contemporary technology comes in. I then collated a range of information on Tarar's style, lexicon, and recurring themes, based on reading "Bahaao" and other research, to "instruct" the AI. I used free and universally accessible AI generative tools (which I deliberately won't name, to stimulate in you that jigyasu bhava – that attitude of curiosity and inquiry so dear to Vedanta – which spurs personal seeking) not for a mere literal translation, but to generate an Italian version that captured its spirit. The result? It exceeded all expectations. I rediscovered intact that narrative brilliance, that unique freshness, that imaginative world bordering on the oneiric, yet so tangible, so imbued with existential questions and mysticism that had captivated me.

"Fakhta" is a stunning work, devoured in one sitting, which dragged me into a nocturnal narrative rush, feverish and almost hallucinatory, evoking in some ways the intensity of Dostoevsky's "White Nights" (and you'll soon see why).

A Taste of "Fakhta" (Without Spoilers)

We are in Moscow, 1957, during the Fifth World Festival of Youth. Our young narrator, a Pakistani student in Nottingham, is catapulted into this contradictory metropolis, a symbol of a world split by the Iron Curtain but animated, in those days, by a utopia of global brotherhood. The epicentre of the story is the night of the festival in Red Square, a chaotic and grand celebration that transforms into a surreal "masked ball." The protagonist, initially an observer, is sucked into a whirlwind of encounters with enigmatic masked creatures disguised as animals: an imposing bear, a sharp-eyed eagle, a philosophical python, even a dancing skeleton and an enigmatic owl.

AI Video by Author (Genmo)

Mast Mast Dam Mast - Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan - In album: Qawwali Night

These figures bother him, question him, challenge him on his identity and the very meaning of reality. Tarar masterfully plays with this weird ambiguity: are they really talking animals, projections of the mind, or masked people embodying ancestral archetypes and social forces? The line is deliberately blurred, leaving the reader in an atmosphere of mystery. The "Dove" (Fakhta) of the title is a silent yet central presence in this night of transformations and confrontations.

Layers of Reading: Masks, Mysticism, and Society

The beauty of "Fakhta" lies in its thematic polyphony:

Pirandellian Masks and Homogenization: The theme of the mask is obsessive. The physical one, certainly, but above all the existential one. We are told: "Tonight, every person participating in this festival must wear a mask." The narrator is forced to wear a rabbit mask: "Now you are not a human being, but a rabbit!", suffering the imposition of an identity not his own. He reflects bitterly: "The mask is a useful thing... It doesn't matter how despicable and horrible one is inside, the mask confers a personality that keeps the true form hidden from the world." A powerful reflection on the pressure to conform and the loss of the "true self."

Sufi Mysticism and Psychedelic Visions: The festival in Red Square transcends simple celebration. It becomes an almost shamanic ritual. The central bonfire (Alao) takes on mystical connotations, reminding the narrator of the Festival of Lights (Mela Chiraghan) dedicated to the Sufi saint Madho Lal Hussain in Lahore: "The heat of the bonfire penetrates my cheeks... My eyes are red, my feet are covered in dust... Today is the festival of Madho Lal Hussain... My true self..." The falling of masks under the fire's heat becomes a collective revelation: "Due to the heat of the bonfire, the masks began to fall from the faces... Their true form was being revealed. Their disguise... their charade was over." The entire sequence has a visionary, almost psychedelic aura.

Socio-Political Context (1957): The novelette is perfectly situated in its time. We are at the height of the Cold War, in Moscow, the heart of the Soviet Union. Pakistan, born just ten years earlier from the painful Partition, is seeking its geopolitical place. The narrator clashes with the Pakistani establishment's distrust of the USSR, embodied by the Prime Minister's threatening warning to the young delegates: "Woe! If any Pakistani boy dares to mention Moscow! Russia is our enemy... anyone... who establishes relations with the Russians is a traitor to the homeland... you will see how you are treated." The Youth Festival thus becomes a complex stage for ideological tensions and hopes for dialogue.

The Echo of War and the Cry for Peace: The account of the old man met at the Minsk station is one of the most powerful and heartbreaking moments. It is not just personal grief for lost sons, but a universal warning against the senselessness of war, made even more poignant by the historical context (World War II still vivid in memory): "'All five were killed by the Nazis during the Second World War... You are exactly like my youngest and most beloved son... My son, war is an extremely terrible thing... I have seen its devastation. I have one request... I am your father... Never allow war to happen. For the sake of your future children, always save the world from war.'" Words that weigh like boulders, today more than ever.

The Dove as a Symbol of the Homeland: The enigmatic figure of the Dove (Fakhta) becomes charged with profound symbolic meaning for the narrator. It becomes an embodiment of his distant land, of nostalgia, of a fragile and melancholic identity: "And then it also reminded me of that distant village in Punjab... where two symbols of the sultry afternoon always haunted me... the sad 'koo ko koo' of the solitary dove perched on the thorny kikar tree. Homesickness made me extremely sad. I wanted to be with this girl... with this dove... It was the symbol of my homeland. The lonely and sad dove."

"Fakhta": A Bridge Between Past and Present

Written almost seventy years ago, this novelette vibrates with surprising relevance. The masks imposed on us, the struggle for authenticity against homogenization, the fear instilled to render us helpless (the rabbit!), the long shadow of war: these are themes that speak directly to us today.

The experience with "Fakhta" reinforces my conviction in the revolutionary potential of AI as a bridge between cultures. How many voices like Tarar's are still waiting to be heard beyond linguistic borders? Immersing oneself in these narratives is an act of resistance against cultural flattening, a way to breathe fresh air and broaden our horizons.

I urge you with all my heart to seek out this novelette. You can find information about "Fakhta" on Goodreads at this link: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/32827889-fakhta. The invitation is to procure it, perhaps try translating it with the tools available today or urge for its publication, and above all, to read it. It is a flash of literary genius, a brief but unforgettable journey that demonstrates the greatness of Mustansar Hussain Tarar from his earliest works.

Thank you for reading and your jigyasu bhava.

Feel free to leave a comment.

I have woven tales for anyone who cares to read them. My books await you on Google Books.

Feel free to contact me.

I would be honoured if you considered subscribing to the Premium Contents of my Vedanta Substack and leaving feedback, comments, and suggestions on this page and by writing to me at cosmicdancerpodcast@gmail.com.

Visit my BuyMeACoffee page.

Thanks for reading.