Ashoka the Great: The First And Unique Mass Communication for Peace in History.

Propagating Nonviolence: Ashoka's Edicts as Ancient Moral Manifestos.

📢 **Exciting News: Elevate Your Experience with Premium Benefits!**

Now, I'm thrilled to unveil an exciting development—we're introducing premium paid subscriptions to Vedanta Substack! By becoming a paid subscriber, you not only enhance your experience but also play a crucial role in supporting the continuation of our exploration.

Vedanta Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

🔓 **Unlock Exclusive Benefits as a Paid Subscriber**

As a paid subscriber, you'll enjoy a range of exclusive benefits:

- Access to in-depth posts with special recommendations for further study.

- Personal invitations to exclusive chats or podcast interviews on captivating topics, featuring multiple thinkers simultaneously.

- The opportunity to propose the publication of your articles and essays on Vedanta Substack.

- Invitations to Vedanta retreats and events offering a deeper exploration of spiritual and philosophical realms.

Image by Author

We are in the 3rd century BC, and India is dominated by an empire that extends from the eastern border of Iran to Bengal and Assam, and from the Pamir to the Deccan. It is the Maurya empire, founded by Chandragupta and brought to its height by his nephew Ashoka, the third sovereign of the dynasty. Ashoka is a fearsome warrior, who has subdued all his enemies by force of arms. But an event will radically change his life and his worldview: the Kalinga war, one of the bloodiest in ancient history.

In 260 BC, Ashoka decided to invade the kingdom of Kalinga, located in present-day Orissa, to further expand his dominion. The war lasted two years and ended with a crushing victory for Ashoka, but at a very high price: over 100,000 dead among the soldiers and 150,000 among the civilians, according to the most conservative estimates. Ashoka walks the battlefield, observing the death and destruction caused, and feels a profound change of mood. He realizes that war brings only suffering and pain and that conquest is not worth sacrificing so many human lives. He repents of his violence and decides to embrace Buddhism, the religion founded by Siddhartha Gautama, the sage who taught the path to liberation from the cycle of rebirth.

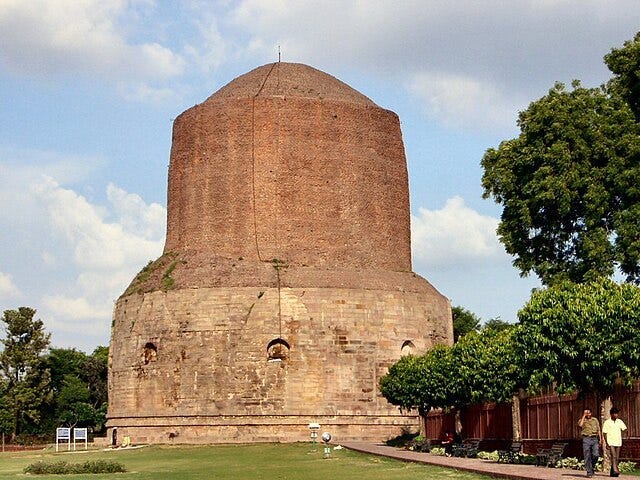

From that moment on, Ashoka radically changed his policies and his style of government. He gives up war and dedicates himself to peace, justice and the well-being of his subjects. He developed the concept of dhamma, which means virtuous social conduct, based on the moral and religious principles of Buddhism. He promotes tolerance and respect among different faiths, the protection of animals and generosity towards the poor and needy. He spread Buddhism throughout his empire and beyond, sending missionaries to various regions of Asia, such as Syria, Egypt, Greece and China. He builds or restores thousands of stupas, which are stone structures containing the relics of the Buddha or other Buddhist monks. Above all, he has messages communicating his laws and principles engraved on pillars, rocks or caves, which are known as the Ashoka edicts.

Terence McKenna's Call for a Return to the Archaic: A Vedantic Response.

📢 **Exciting News: Elevate Your Experience with Premium Benefits!** Now, I'm thrilled to unveil an exciting development—we're introducing premium paid subscriptions to Vedanta Substack! By becoming a paid subscriber, you not only enhance your experience but also play a crucial role in supporting the continuation of our exploration.

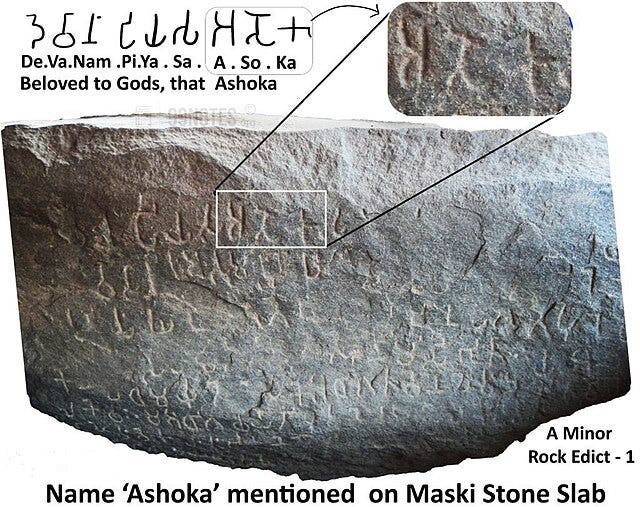

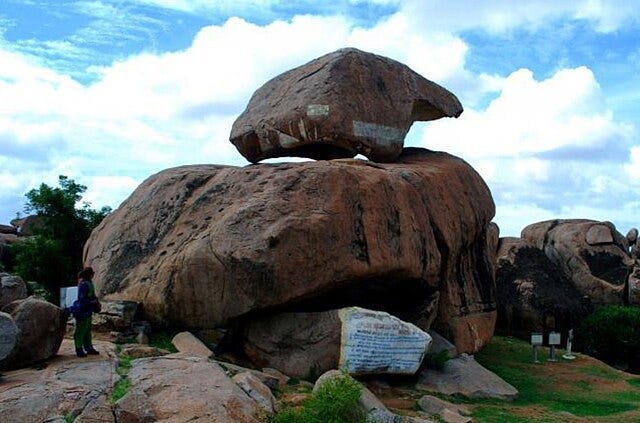

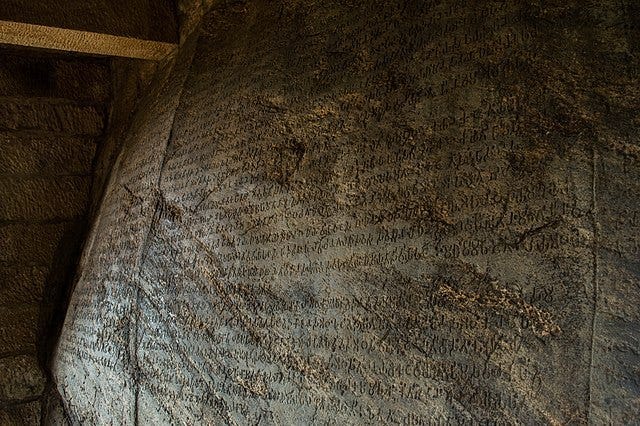

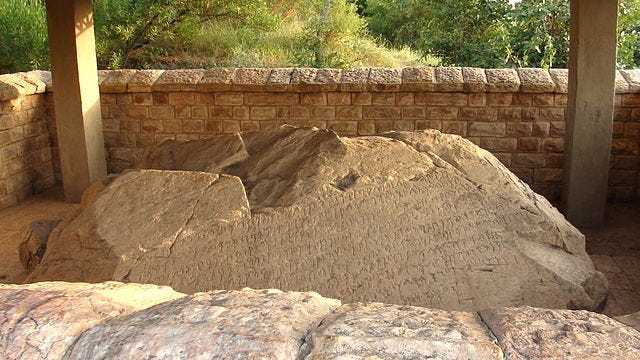

Edicts

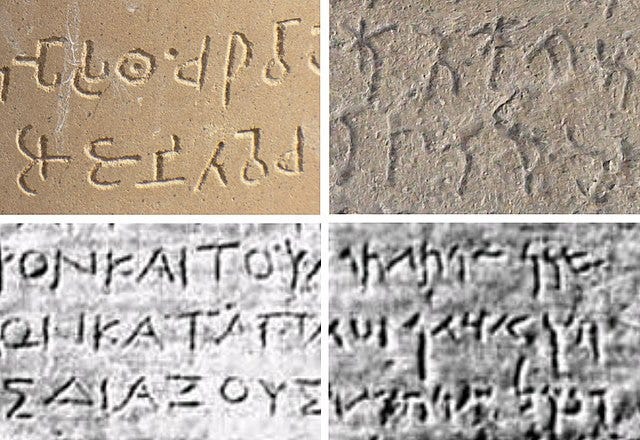

The Ashoka edicts are a unique testimony in the history of antiquity because they represent the first and only example of mass communication for the promotion of peace and non-violence. The edicts were inscribed on polished sandstone surfaces, including boulders and monolithic pillars. The durable stone was used for both the slab structures and columnar formats, with inscriptions on broad flat facets. This created robust architectural platforms to prominently display Ashoka’s messages across his vast territory. These innovative ideas were inspired by the figure of the Buddhist monk Upagupta, whose role we will explore later. Ashoka uses simple and direct language that can be understood by all, and addresses his subjects as if they were his children, calling himself “Beloved by the Gods” and “with a kind gaze”.

The edicts were written in different languages, such as Magadhi, Sanskrit, Greek and Aramaic, depending on the areas where they are located. The edicts were present in various places in Asia, especially in northern and central India, but also in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh.

The geographical distribution of the edicts reflected the extent of the Mauryan empire under the reign of Ashoka, which was estimated at around 5 million km2, according to some sources. This made it one of the largest empires of its time and in the history of India.

Ashoka is considered one of the greatest rulers in history, not only for his military and political might but also for his wisdom and humanity. His example has inspired generations of leaders and pacifists, who have recognized him as a model of conversion and virtuous behaviour. His name is still honoured today in many countries, and his symbol, the Ashokan capital, depicting four lions looking in four directions, has become the emblem of modern India.

As for the locations of Ashoka’s edicts, here are the nations where they are found:

Minor rock edicts: there are 14 in total and they are carved on rocks. They are located in India, except for Mahasthan which is located in Bangladesh.

Major rock edicts: there are 14 in total and they are carved on rocks. They are located in India, except for Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra which are located in Pakistan.

Pillar edicts: there are 7 in total and they are engraved on monolithic sandstone columns, surmounted by the Ashokan capital. They are located in India, except for Lumbini and Nigali-Sagar which are located in Nepal.

Inscriptions in Greek or Aramaic: there are 4 in total and they are written in Greek or Aramaic. They are located in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Dedication inscriptions: there are 3 in total and they are carved in the Barabar caves for the ascetic Ajivika sect. They are located in India.

Languages and Scripts of Ashoka’s Edicts

As aforementioned, Emperor Ashoka published his letters and ethical precepts, known as Edicts, in three languages: the local Prakrit dialects, Greek of the neighbouring Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and Aramaic, the official tongue of the former Achaemenid Empire. The Prakrit texts displayed regional variations, from Gandhari in the northwest to Ardhamagadhi in the east, the administrative language at court. The informal Prakrit wording suggests they were meant for broad comprehension across Ashoka’s domains.

Four scripts conveyed Ashoka’s message. Brahmi and Kharosthi conveyed the Prakrit versions in the central areas and modern-day Pakistan respectively. Where Greek or Aramaic was used in the northwest, appropriate scripts did so. After the fall of the Harrapan Civilization, Ashoka’s inscriptions represent Indian writing’s reemergence; Prakrit remained India’s main inscriptional idiom for centuries partly due to their influence before Sanskrit’s 1st century CE ascent.

The Edicts’ Ethical Content

Ashoka’s “Dharma” denotes doing good, respecting others, giving, and purity. He articulated it through the Prakrit Dhaṃma, Greek Eusebeia, and Aramaic Qsyt, translating the concept among cultures.

Moral Guidance

Ashoka declared that Dharma meant minimizing misdeeds and maximizing good actions, charity, truthfulness, and high character. He foresaw Dharma’s glory spreading globally through such virtues.

Benevolence

Ashoka leveraged power to aid his subjects and transform mindsets and conduct for good, believing Dharma encompassed righteous leadership.

Clemency Towards Captives

Ashoka insisted on judiciary consistency but caution and lenience in sentencing, regularly pardoning prisoners so relatives could plead for them or they could repent with charity and fasting for positive rebirth. While punishment was unavoidable, redemption was ideal.

Animal Welfare

As the first Indian ruler uniting governance with ecosystem conservation, Ashoka enforced wildlife protection and even relinquished the royal hunt after embracing Buddhism. His pillar decrees cite fines for poaching in royal reserves, proving rule-breaking persisted despite legal deterrents against common overhunting, tree-felling and fires. But he made unprecedented compassionate gestures like safeguarding rare birds and animals.

Religious Guidance

Buddhism

Rock and pillar edict references to Buddhism and Shakyamuni Buddha appeared only after Ashoka openly identified as Buddhist. Beyond spreading Buddhist ethics, Ashoka insisted monastics frequently read and contemplate select Buddha discourses he admired. His personal devotion also emerges through past Buddha memorials he honoured.

Afterlife Beliefs

Ashoka indicated good deeds brought infinite spiritual merits. He portrayed mindfulness, obedience, avoiding sin and energetic virtue as prerequisites for present and future well-being.

Religious Exchange

Believing shared ethics underlined all faiths, Ashoka advanced sectarian tolerance and understanding, denouncing the notion of spiritual superiority. He aspired to multi-faith erudition, dialogue and cooperation.

Welfare at Home and Abroad

Ashoka’s records reveal extensive domestic healthcare, travel comfort, and faith monitoring for societal welfare. They even document transmitting medical know-how and treatments to neighbours like the Seleucid King Antiochus.

Healthcare Provisions

From herbs to roots, Ashoka ordered medicinal flora cultivation and distribution wherever lacking. Tree planting and well digging improved travel conditions and public health.

Hospitality Infrastructure

Ashoka’s mass construction of steps and wells connected locales, building infrastructure along roads between towns. Travellers and animals benefitted from shady trees, fruit, water and rest. While prior rulers allowed pleasure, Ashoka focused on fostering morality through public works enhancing comfort.

Faith Officers

Thirteen years after his anointment, Ashoka created provincial Faith Superintendents. They promoted sectarian learning, morality and welfare for spiritual adherents across social strata, even beyond borders like the Hellenic Northwest.

Historic Sites

When visiting Lumbini in modern Nepal, Ashoka confirmed Sakyamuni Buddha’s birthplace, the earliest epigraphic use of “Buddha’s” revered epithet. This tour occurred during his 21st reign year by his dating.

The 84,000 Stupas of Peace: Ashoka and Upagupta’s Legacy of Nonviolence

As aforementioned, in the 3rd century BCE, the Indian Emperor Ashoka undertook a historic mission — to spread a message of nonviolence, compassion and unity across his vast dominion through the creation of 84,000 magnificent shrines. Behind this monumental endeavour lay the visionary guidance of a Buddhist monk named Upagupta. Their collective legacy stands as an enduring testament to the power of art, architecture and moral example to promote peace.

Seeking spiritual direction, he turned to the sage Upagupta — one of the most influential Buddhist monks of that era. Upagupta was a masterly teacher who helped introduce Emperor Ashoka to the philosophy of nonviolence and the principles the Buddha had preached several centuries earlier. Under Upagupta’s guidance, Ashoka embraced the dharma — a spiritual, ethical and political system based on compassion, temperance and rationalism.

Hoping to propagate these ideals across his dominions, Emperor Ashoka, with input from Upagupta, conceived an inspired plan — to build 84,000 towering dome-shaped shrines known as stupas. This special number was imbued with deep significance in ancient Indian cosmology, representing the highest fulfilment of a virtuous mission. The stupas would serve as monumental three-dimensional symbols to inspire moral conduct, harmony and spirituality among Ashoka’s vast multi-religious populace.

Built of stone and brick, the shrines stood up to 80 meters tall, looming large over towns and trade routes across South Asia. Others were modest roadside pavilions for travellers to rest under. But all physically signified the central tenets of Ashoka’s public philosophy — his dedication to nonviolence (ahimsa), tolerance of difference, and the ethical treatment of all humans and animals.

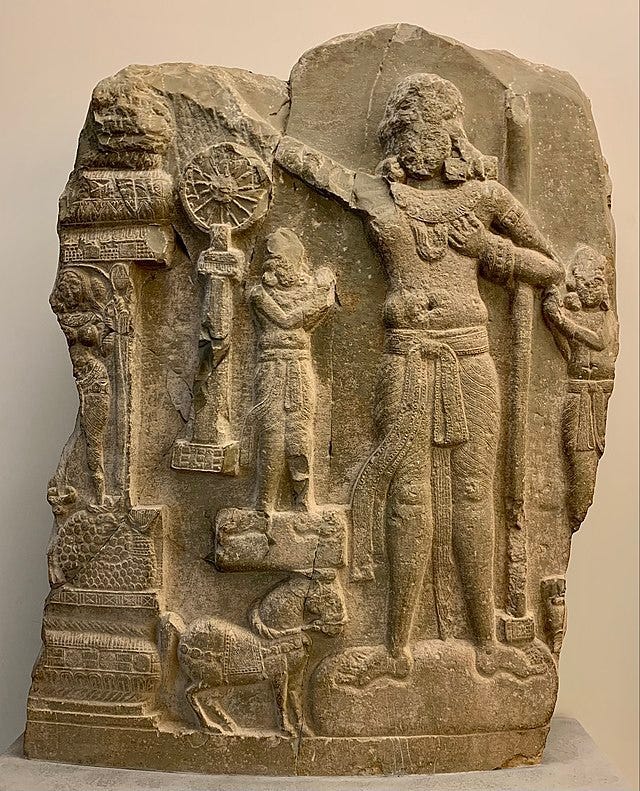

A small stone or brick building, varying in size but generally not too large (a few square meters). Inside would be a small room, often containing a statue/image of Buddha or other Buddhist religious figures. They could also have bas-reliefs on the walls depicting Buddhist religious scenes. Around them, there was often a small garden or open space. They were usually built near villages, along main roads or in panoramic locations, to be easily accessible. Their purpose was to spread the message of Buddhism across the empire, while also offering a place for prayer and meditation. Then, sanctuaries in structure but disseminated in large numbers across the realm, to reach as many people as possible and promote the Buddhist values of non-violence and compassion.

Upagupta himself advised the Emperor on where major stupas should be positioned for maximum spiritual impact and visual effect. Architectural remnants suggest the monk encouraged mathematical harmony and sacred geometry in their design. Upagupta also helped Ashoka inscribe his famous Pillar Edicts which were placed around the empire, explicitly outlining the Emperor’s new policies of justice, mutual respect and ecological concern.

While Ashoka provided supreme administrative oversight for this mammoth building project, Upagupta helped shape the core ethical vision. Together their collaborative efforts made thousands of stupas, one of history’s most successful campaigns to promote values of nonviolence through art and symbolism on a society-wide scale.

Surveying the sites today, only fractions of the original stupas still stand intact, scattered across South Asia from modern-day Pakistan to Bihar. But their aesthetic beauty and architectural majesty continue to inspire awe and wonder. The structure in Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh with its intricate stone carvings depicting the Buddha’s life; or the towering 52-meter dome of the Mahastupa relic shrine guarding the Buddha’s remains — these active Buddhist monuments still emanate a palpable spiritual presence.

“His Majesty the holy and gracious king has built many stupas, which are the houses of the Buddhas. The stupas are decorated with statues and sculptures of Buddha and his disciples. The stupas are places of worship and meditation for the faithful. The stupas are also sources of benefit for the animals and plants that live around them.”

“His Majesty the holy and gracious king has ordered the construction of many rock edicts, which are inscriptions containing his moral and religious teachings. The rock edicts have been erected in various places in his empire, to make known his kingdom and his faith to the whole world. The rock edicts are also testimonies to his generosity towards the poor, slaves, animals and other living beings.”

“His Majesty the holy and gracious king founded the city of Pataliputra, which is the capital of his empire. Pataliputra is a city rich in history, culture and art. Pataliputra is also a city where one can admire many Ashokan stupas and edicts, which show his greatness and wisdom. Pataliputra is a city where one can feel the atmosphere of Buddhism.”

These excerpts are passages attributed to the 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who travelled to India and wrote about the architectural legacy of Emperor Ashoka in his memoir “Da Tang Xi Yu Ji” — “Great Tang Records on the Western Regions”. The above lines describe stupas, rock edicts, and the city of Pataliputra established under Ashoka’s rule in the 3rd century BCE.

Indeed, the stupas remain a testament to the power of art and iconography to propagate virtue across time and culture. Through creative architecture imbued with meaning, Emperor Ashoka helped shift the entire moral tone of one of history’s largest empires away from war and towards tolerance and compassion. His legacy stands as a shining counterpoint to so many later rulers who employed art to glorify conquest.

In our current times of instability and tribal identity, Ashoka and Upagupta’s collaborative example remains highly relevant. It makes us ponder deeply how governments, activists and artists today might also leverage the connective and inspirational power of thoughtful public art, symbolism, urban design projects and architectures of hope. Their Stupas of Peace remind us that the human soul innately yearns for uplifting spaces and symbols that resonate goodness, healing, unity and understanding. Their legacy reinforces how beautiful aesthetics allied to noble ethics can speak across all races, tongues and philosophies to bring more light into the world.

I have woven tales to share, for any who care to read them. My books await you on Google Books. Check also my stories on Medium.com.

I would be honoured if you considered subscribing to the Premium Contents of my Vedanta Substack and leaving feedback, comments, and suggestions both on this page and by writing to me at cosmicdancerpodcast@gmail.com.

Thank you for your precious attention.