Giacomo Leopardi's "Operette morali" [Moral Essays]: Poetry and AI

"Proposta di premi fatta dall'Accademia dei Sillografi": A satirical critique of material progress

The story "Proposta di premi fatta dall'Accademia dei Sillografi" [Prize Proposal Made by the Academy of Syllographers] by the poet Giacomo Leopardi represents an illuminating text of his philosophical and literary masterpiece, the "Operette Morali" [Moral Essays]. While reading these works, composed mainly between 1824 and 1827, I discovered an authentic laboratory of thought by the poet from Recanati, a sharp and disenchanted exploration of the human condition.

The "Operette Morali" are not simple essays, but short compositions, often dialogic, that stage complex philosophical concepts through an elegant, ironic, and sometimes grotesque style. The author addresses universal themes such as happiness, pain, boredom, the relationship between man and nature, progress, and the meaning of history. He does this through clear and sharp prose that dismantles the illusions and conventions of his time, offering a deeply pessimistic vision, but one that is nonetheless rich in points for reflection.

"Proposta di premi fatta dall'Accademia dei Sillografi": a satire of material progress

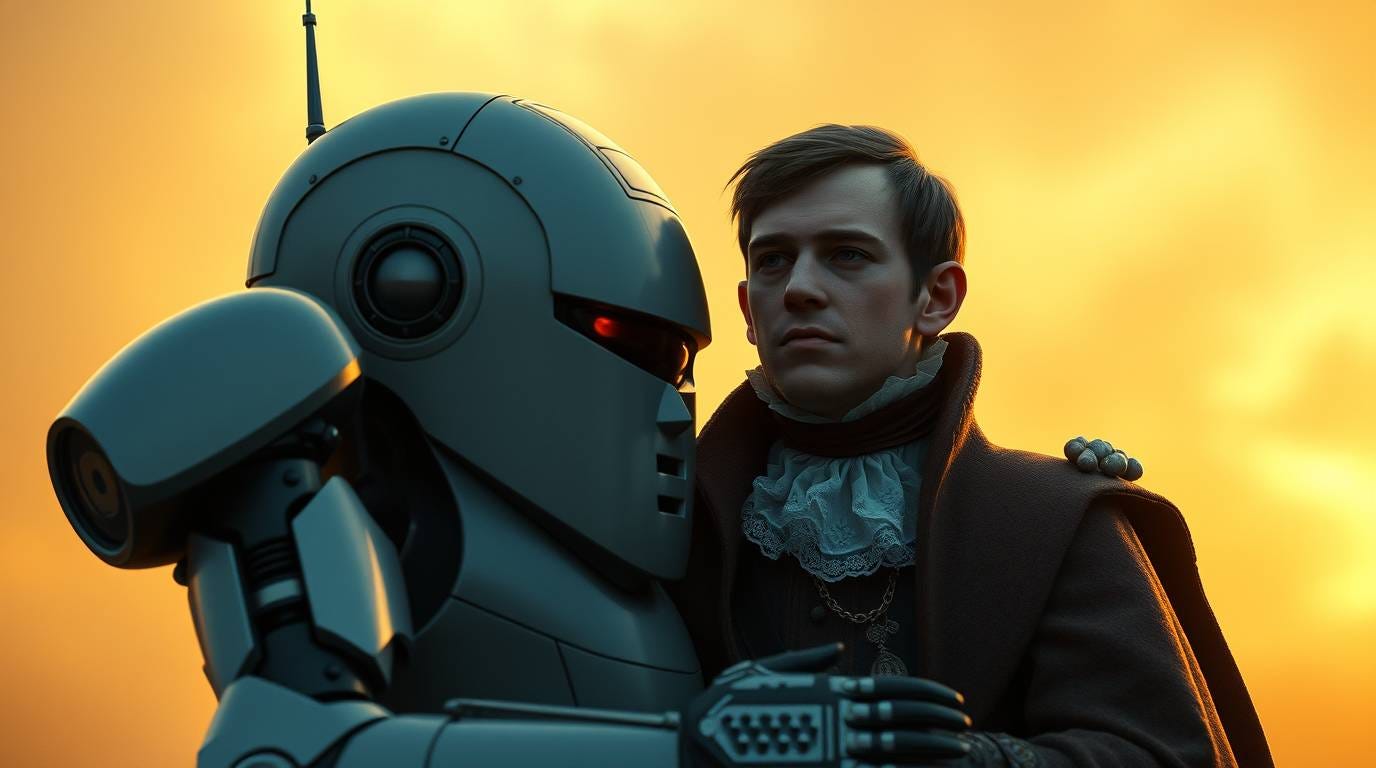

The story "Proposta di premi..." is a perfect example of this approach. The philosopher imagines a bizarre academy of "syllographers" (satirical writers) that announces a competition for the invention of three extraordinary machines, capable of embodying human ideals: a perfect friend, an artificial man devoted to virtue, and an ideal woman.

- The perfect friend: a machine free from human weaknesses, capable of unconditional friendship, without envy, betrayals, or pettiness.

- The steam-powered artificial man: an automaton animated by a noble spirit, capable of magnanimous and virtuous actions, like the heroes of epic poems.

- The ideal woman: a machine that embodies the perfect feminine model, inspired by literary idealizations, like those in Castiglione's "Il Cortegiano" [The Book of the Courtier].

The thinker's intent is not to believe in the real possibility of building such machines. His is a sharp satire of technological progress, which does not necessarily lead to the moral or spiritual improvement of mankind. As we read in the "Proposta": "Essendo adunque manifesto che l'amicizia è una delle cose più necessarie e più rare al mondo, e che gli uomini non si possono quasi tollerare l'un l'altro senza questa, l'Accademia ha giudicato di proporre un premio a chi trovasse il modo di fabbricare una macchina che facesse gli uffici di un amico perfetto." [Being, therefore, manifest that friendship is one of the most necessary and rarest things in the world and that men can hardly tolerate each other without it, the Academy has judged to propose a prize to whoever finds a way to manufacture a machine that performs the offices of a perfect friend.]

The Reference to Virgil: an echo of hope in a disenchanted world

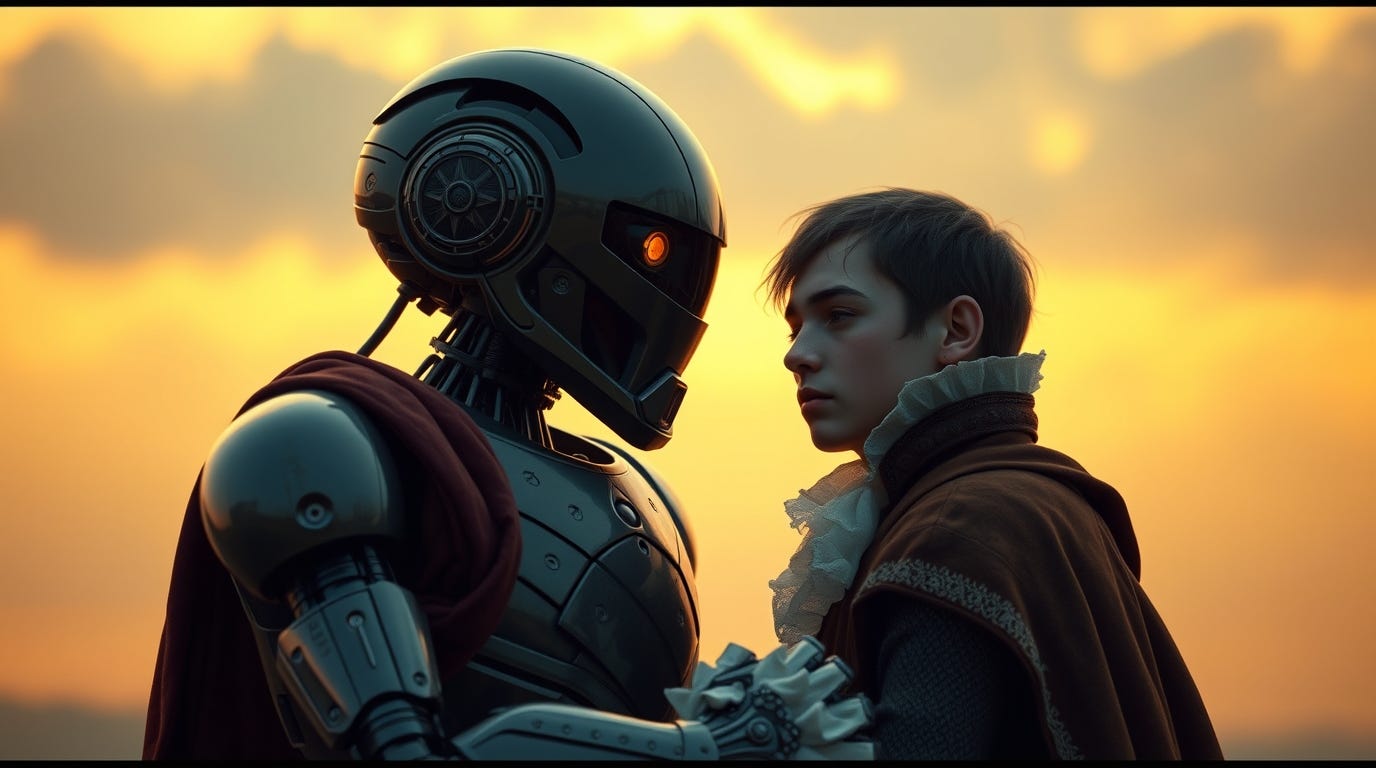

And this is where the reference to Virgil comes into play, a crucial element for understanding the message of the intellectual from Recanati. In describing the prize for the artificial man, the great writer quotes the fourth eclogue of Virgil's Bucolics: "QUO FERREA PRIMUM DESINET AC TOTO SURGET GENS AUREA MUNDO!" [When for the first time the iron age shall cease and a golden race shall arise in all the world!]

This quotation is dense with meaning. Virgil, in his poem, prophesied the advent of a new golden age, an epoch of peace, justice, and prosperity that would end the sufferings of the Iron Age. The author takes up the theme, charging it with new significance. Despite his cosmic pessimism, he seems to want to leave open a small window of hope. Perhaps, through human ingenuity, one could still aspire to a better world, even if not through simple material machines. Later, speaking of the machine that should emulate an ideal woman, the poet writes: "Né anche l'invenzione di questa macchina dovrà parere impossibile agli uomini dei nostri tempi, quando pensino che Pigmalione in tempi antichissimi ed alieni dalle scienze si potè fabbricare la sposa colle proprie mani, la quale si tiene che fosse la miglior donna che sia stata insino al presente." [Nor should the invention of this machine appear impossible to the men of our times, when they think that Pygmalion in very ancient times alien to sciences could fabricate his bride with his own hands, who is held to have been the best woman that has existed until the present.]

AI Today: a new chapter in the dialogue between man and machine

Today, in the era of Artificial Intelligence, this dialogue between Leopardi and Virgil takes on new relevance. The machines that the philosopher imagined have become reality. We have created artificial intelligences capable of performing complex tasks, learning, and creating. But has this progress truly brought us closer to that "golden race" prophesied by Virgil? The poet from Recanati, in the "Proposta", describing the prize for the machine-woman, uses hyperbolic tones: "Assegnasi all'autore di questa macchina una medaglia d'oro in peso di cinquecento zecchini, in sulla quale sarà figurata da una faccia l'araba fenice del Metastasio posata sopra una pianta di specie europea, dall'altra parte sarà scritto il nome del premiato col titolo: INVENTORE DELLE DONNE FEDELI E DELLA FELICITÀ CONIUGALE." [To the author of this machine is assigned a gold medal weighing five hundred zecchini, on which will be figured on one face Metastasio's Arabian phoenix perched upon a plant of European species, on the other side will be written the name of the winner with the title: INVENTOR OF FAITHFUL WOMEN AND CONJUGAL HAPPINESS.]

And so?

But the fundamental question remains the same: will these machines truly make us better? Will they lead us to a new golden age, or simply amplify our weaknesses and errors?

Will we, in the AI era, be worthy of that "gens aurea" prophesied by Virgil and recalled by Leopardi? Will we be capable of using technology not only for material progress but also for authentic moral and spiritual progress?

The reflection of the great thinker offers a precious key to reading for facing the challenges of our time. AI, far from being a mere substitute for humans, can support them in a path of growth, contributing to moral and cultural progress in significant ways. The true "machine" to invent is not something external to us, but an interior transformation, a constant commitment to overcome our limits and aspire to greater humanity, enhancing our cognitive and creative capabilities. Only then can we be worthy of that "golden race" and build a tomorrow where technology and humanity integrate in virtuous harmony. The words of Virgil and Leopardi, two immortal voices that rest close to each other in the Virgilian Park at Piedigrotta in Naples, continue to resonate in the hearts of those who seek a deeper meaning to existence. Even AI, with its infinite possibilities, can become a new source of inspiration, helping us explore new horizons and shape a better future.

Feel free to leave a comment.

I have woven tales for anyone who cares to read them. My books await you on Google Books. You can also check out my stories on Medium.com.

I am eager to participate in research and produce content on Cross-Cultural Philosophy. Considering the many philosophy professors following Learn Vedanta Substack from universities across the five continents, I would be truly honoured to be involved in projects, as I have been recently approached. Please feel free to contact me.

I would be honoured if you considered subscribing to the Premium Contents of my Vedanta Substack and leaving feedback, comments, and suggestions on this page and by writing to me at cosmicdancerpodcast@gmail.com.