The Poet in the Pit: My Short Story about Francis Petrarch in Naples

Based on the true events of Petrarch's time in Naples

In the *Lettere familiari di Francesco Petrarca* (Book V, letters III and VI) [*Familiar Letters of Francis Petrarch*], I immerse myself in the paradox that the poet unknowingly reveals in his Neapolitan experience of 1343, during the days following the death of Roberto d'Angiò [Robert of Anjou]. The filthy and the sublime are two sides of the same coin, an endless dialogue that Vedanta has taught me to recognize. In his accounts, I no longer see just the degradation that so disturbed him, but I glimpse a terrifying beauty - that ultimate truth where even the grotesque is a manifestation of the absolute. It is precisely in the horror of Naples that the prodigy reveals itself: the unity that embraces and transcends every dualism, even the most heart-wrenching.

Commissioned by Pope Clement VI and Cardinal Colonna of Stigliano to manage the succession to the throne, Petrarch found himself immersed in a reality that sharply contrasted with his ideal of beauty and harmony. On one side, the court, with the grotesque figure of a jester who usurped the name of the deceased king, described with fiery words in Petrarch's own words:

"un animale a tre piedi, scalzo, scappucciato, superbo della sua povertà, flaccido per libidine."

[a three-legged animal, barefoot, hoodless, proud of his poverty, flaccid with lust].

On the other side, a popular and violent Naples manifested itself, especially in a very specific area: Carbonara. This was not a simple neighbourhood, but a place outside the city walls, an area designated for waste disposal, a receptacle for criminals and a theatre of violence. It was a degraded area, in short, that lent itself well to bloody spectacles like those Petrarch witnessed. And right here, in this squalid and dangerous context, the poet describes with horror the spectacles he witnessed:

"In pieno giorno, alla vista del Popolo, al cospetto del Re, in questa città d'Italia con barbara ferocia, si esercita l'infame gioco dei Gladiatori; e come sangue di pecore, l'umano sangue si sparge, e, plaudendo l'insano volgo affollato, sotto gli occhi dei miseri genitori si scannano i figli."

[In broad daylight, given the People, in the presence of the King, in this Italian city with barbaric ferocity, the infamous game of Gladiators is practised; and like sheep's blood, human blood is spilt, and, with the insane crowd applauding, sons are slaughtered before the eyes of their miserable parents].

But not only that. On another occasion, still in Carbonara, Petrarch witnesses a murder in the middle of the street, a scene that deeply disturbs him:

"A tanto concorso di gente, e a tanta attenzione d'illustri personaggi sospeso, fiso io guardava aspettando di vedere qualche gran cosa, quand'ecco come per lietissimo evento un indicibile universale applauso s'alza alle stelle. Mi guardo intorno e veggo un bellissimo garzone trapassato da freddo pugnale cadermi ai piedi. Rimasi attonito, inorridito."

[With such a crowd of people, and such attention from illustrious personalities suspended, I watched intently expecting to see some great thing, when suddenly as if for a most joyous event an indescribable universal applause rises to the stars. I look around and see a most beautiful youth, pierced by a cold dagger, falling at my feet. I remained astonished, horrified].

Starting from these words, from this direct testimony of the poet, I imagined a fictional encounter that could embody his deep discomfort, his crisis in the face of a reality so crude and distant from his inner world. This story therefore arises from my interpretation, an attempt to give narrative form to an experience that deeply marked the poet, interweaving historical facts, his own words, and my imagination. I hope that this exploration of a distant Naples, filtered through Petrarch's sensibility, can engage you as much as it has fascinated me. Happy reading.

“The Poet in the Pit”

The sun beat down like a curse on Carbonara, a teeming gut on the margins of Naples in 1343. The air, dense with effluvia of putrid fish, acrid sweat, and pungent spices, vibrated with a deafening murmur, a continuous bass of incomprehensible dialects, hoarse shouts, and coarse laughter. Francis Petrarch, back in the city after the death of King Robert the Wise, observed everything with different eyes from those of the young poet who two years earlier had received his poetic laurels right here. Now, following the Angevin delegation in those turbulent days of succession to the throne, he felt like an intruder, an anomaly wrapped in his fine wool robe amidst that pandemonium of beggars and shopkeepers. The Carbonario, as they called this area outside the ancient walls, had always been an ill-reputed place, but now, in the power vacuum following the death of the patron king, it seemed to have sunk into an even darker abyss.

Then, silence. A clean cut through the chaos, followed by a guttural rattle. A young man dragged forcibly to the centre of the street, was finished off with dagger blows. The blood, thick and dark, spread on the dust like a black flower. Petrarch, with his stomach in turmoil, saw something even more disturbing than the murder itself: the ecstasy painted on the faces of the bystanders. Thunderous applause, shouts of approval, as if at the theatre, but a theatre of horror.

Beside him, Giovanni, a seasoned and cynical courtier, shook his head with a resigned expression of disgust. A corpulent man, with an unkempt beard and a squinting eye, approached Giovanni, gesturing animatedly and speaking in a thick Neapolitan dialect, peppered with Gallicisms and vague Arabic reminiscences.

"Guagliò, che spettacolo! 'Na vera festa!"

[Boy, what a spectacle! A real feast!]

Giovanni answered him in a mixture of broken Italian and French:

"Sì, monsieur... eh... capisco... ma... un po'... forte, no? Trop fort, direi..."

[Yes, sir... uh... I understand... but... a bit... strong, no? Too strong, I'd say...]

The man laughed heartily, slapping him on the shoulder so hard it almost made him stagger.

"Forte? Ah! Chisto è niente!"

[Strong? Ah! This is nothing!]

Petrarch, with his heart beating wildly, asked Giovanni what they had said. "Nothing important," replied the courtier with a shrug. "Just complimenting the spectacle. They use a mixture of dialect, French, and sometimes even some Arabic words. Here they speak however they can, the important thing is to understand each other."

At that precise moment, a fat and flushed courtier with a perpetually affected air, made his way through the crowd, rudely pushing the bystanders.

"Jatevénne, fetienti!"

[Get away, stinking ones!]

He shouted in dialect, before turning to Petrarch with a honeyed smile. Then, in a stentorian voice, he declaimed in macaronic French:

"Laissez passer! Laissez passer le poète! Le chantre de la beauté!"

[Make way! Make way for the poet! The singer of beauty!]

Finally, addressing the crowd with aristocratic disgust, he concluded in Italian: "Stay away from him, rabble! This is not shit like you! This is the poet of beauty!"

A thin little voice distracted him. A girl, no taller than a meter, dressed in dirty rags but with two blue eyes of an almost unreal purity, stared at him intensely. Her hands were filthy with earth, but her gaze was clear as spring water. Suddenly, with a confidence that threw Petrarch off balance, the girl took his hand. With an unexpected gesture, the royal guards stepped forward, ready to push her away roughly, but Petrarch stopped them. "Leave her be," he said firmly, in a voice he didn't even recognize himself.

The girl dragged him by the hand through a labyrinth of even narrower and darker alleys, where the smell of urine and garbage mixed with putrid odours. The guards, perplexed but obedient to the poet's order, followed at a distance, their hands on their sword hilts. They arrived in front of a dilapidated building, the windows barred and the walls peeling as if about to collapse. The girl made him enter.

Inside, the dim light filtering through a crack in the roof revealed an even more desolate spectacle. An emaciated and dirty boy sat on the ground. He had no legs, truncated at the knees, but on his hollowed face shone a disarming smile. He extended a hand to Petrarch. The girl approached the poet's ear and whispered something in a dialect so thick and archaic that Petrarch didn't understand a single word.

"I don't understand," he said, with a thread of voice.

One of the guards, a middle-aged man with a face marked by battles, offered to translate. The girl repeated the phrase, carefully enunciating the words:

"Che ce ne facimmo d''a bellezza si già simmo muorti?"

[What do we do with beauty if we are already dead?]

The guard translated with a grave voice: "She says: 'What do we do with beauty if we are already dead?'"

Just at that moment, while the girl's words resonated in the dense and still air, a ringing voice broke the silence: "Make way! Make way for the poet of beauty! The singer of love and grace!" It was another member of the court, a pompous man trying to impress the crowd.

Petrarch turned pale. His gaze, at first bewildered, transformed into terror, then into a dull and piercing pain that streaked his face with bitter tears. Beauty, his ideal of beauty, shattered against the crude reality of misery and death, incarnated in that mutilated boy and those terrible words.

At that instant, a fierce growl tore through the air. From the alley came the sound of a savage scuffle. Stray dogs were fighting furiously over a macabre trophy: a human arm, still dripping blood, torn from who knows where, a horror added to horror, forever sealing in Petrarch's mind the image of a dark and ruthless Naples.

A corpulent woman leaned out from an old window, showing her naked breasts, rosy and extraordinarily abundant. A dark butterfly landed on a nipple. "Kyow!", the strong and hoarse cry of a seagull broke the sick quiet. Petrarch closed his eyes.

Feel free to leave a comment.

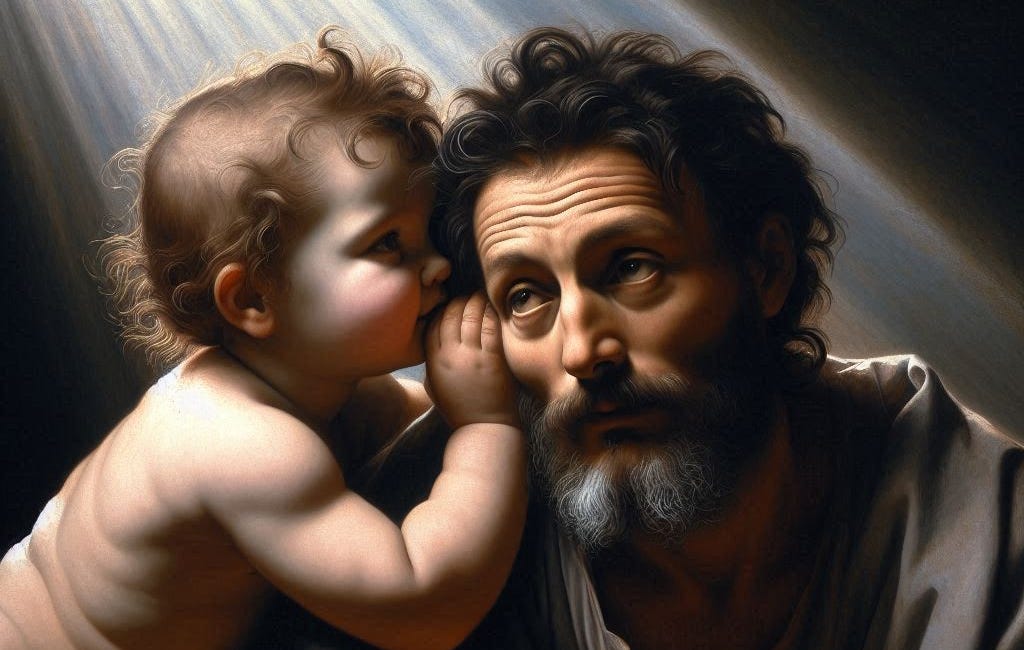

Christ Child Whispering to Caravaggio's Ear

I wrote this fictional story inspired by the eternal principle "As in Heaven, so on Earth," weaving together the divine and the material, peaks of art with Neapolitan folk wisdom. The story takes place in 1607 when Caravaggio painted "The Seven Works of Mercy" for the Pio Monte de…

Vivaldi's Vision in Naples: My Short Story

Fascinated by the figure of Antonio Vivaldi and in love with the vibrant atmosphere of Naples, I have woven together reality and fiction in this story. I imagined an extraordinary encounter, an unexpected inspiration that could shake the genius of the Red Priest, transporting him into an unexplored sound universe. I hope this foray betwee…

I have woven tales for anyone who cares to read them. My books await you on Google Books. Check also my stories on Medium.com.

I am eager to participate in research and produce content on Cross-Cultural Philosophy. Considering the many philosophy professors following Learn Vedanta Substack from universities across the five continents, I would be truly honoured to be involved in projects, as I have been recently approached. Please feel free to contact me.

I would be honoured if you considered subscribing to the Premium Contents of my Vedanta Substack and leaving feedback, comments, and suggestions on this page and by writing to me at cosmicdancerpodcast@gmail.com.

GIFT A LEARN VEDANTA SUBSTACK SUBSCRIPTION.

Thanks for reading.