Threads Through Time: Lessons on Land and People from 13,000 Years in Israel. Focus on Samskaras and Vasanas.

How Shifting Roots Left Imprints on the Soul's Samskaras.

This piece traces the interwoven tapestry of Israel's history across 13,000 years, from roaming hunter-gatherer tribes to complex agrarian civilizations. It explores how this long transition left indelible marks on the human conscience that continue to shape mindsets today. The narrative arc serves to illuminate the subtle threads of identity, belief systems, and social dynamics that evolved in tandem with lifestyles centered first on foraging patterns before gradually transforming into settled farming communities.

Through the lens of samskaras – defined in Vedanta as the deepest impressions arising from actions and experiences – and vasanas – the latent tendencies conditioned by these subconscious imprints – the article aims to examine how generational habits, outlooks, and values morphed in the cauldron of adaptation. By surfacing how transformations in relating to land and community reinforced certain worldviews with each era, the piece connects the dots between humanity's early beginnings and present-day tensions around resources, power, and group identities. Ultimately, an awareness of this history points to collective wisdom that can heal divisions by honoring the diversity of stories woven into Israel's social fabric across the millennia.

Part 1 - The Long, Slow Path to Farming

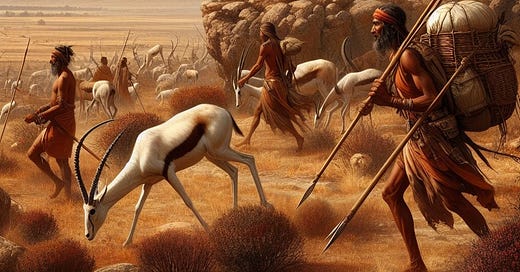

Imagine this - it was 13,000 years ago in what we now call Israel. You're part of a small tribe that moves around foraging for plants and hunting gazelle with spears. You carry everything you own on your back since you don't stay in one spot long. The older kids help the adults dig up wild tubers, gather nuts and cereals, care for infants, and set up simple windbreak shelters at each camp. It’s been this way for countless generations.

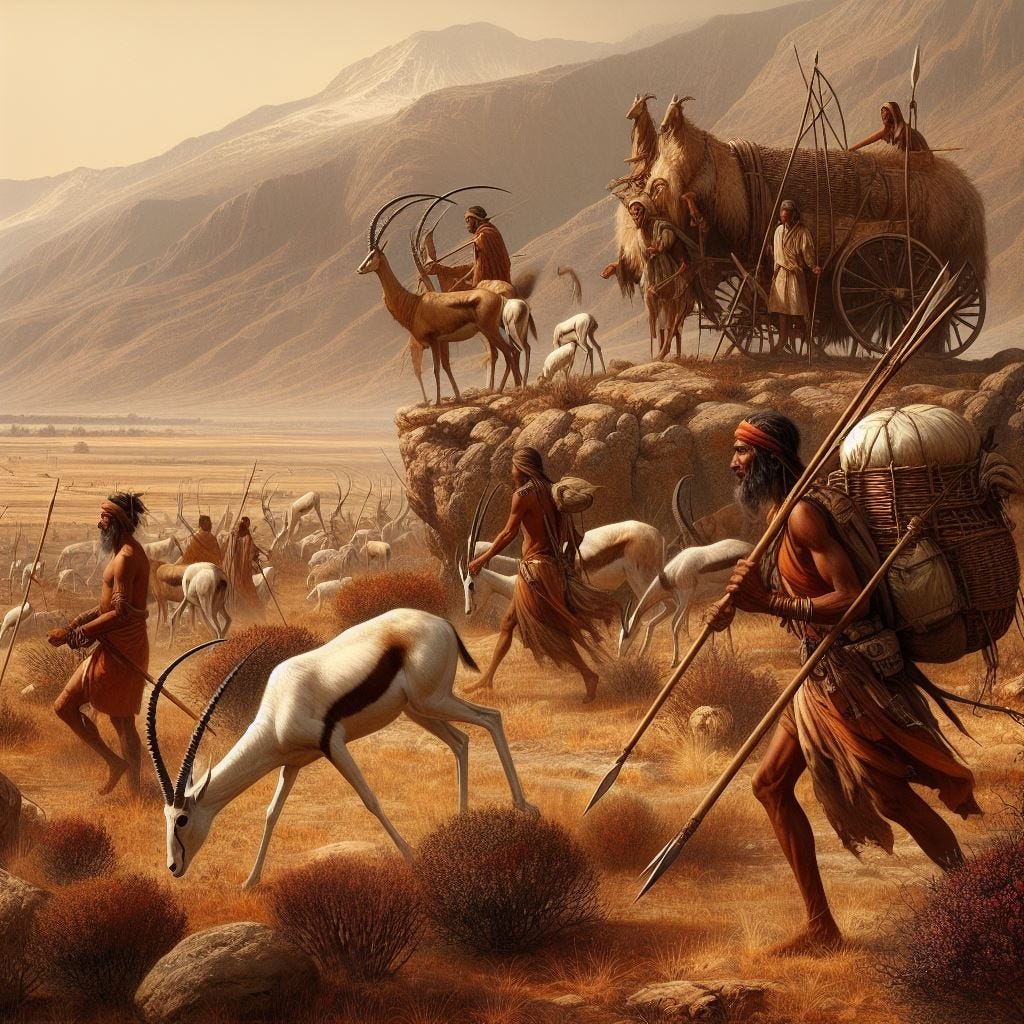

Now jump ahead 3000 years later. Tribes in this area start settling into more permanent villages half the year or longer before moving camps. In these base settlements, you build more solid mudbrick houses. Women grind wild grains into flour to make flatbread using new specialized tools like mortars and pestles. Men continue to track and hunt gazelle across the landscapes during parts of the year. You also gather surplus wild cereals to store for lean times.

Another few generations pass. By 10,000 years ago, these semi-permanent settlements had grown into sizable villages of 50-300 people living together most of the year. Harder stone and mudbrick roundhouses replace the old brush shelters. Crafts like jewelry, woven baskets, polished bone utensils, and stone tools become specialized skilled trades improving every year.

Over these thousands of years, the knowledge of plants, animals, and the land builds up. By 9000 years ago, grains showed changes from wild types, becoming larger seeded or faster growing. Soon, the tribesmen select the best sheep, goats, and eventually cattle to breed. And just like that (over 3000 years!), agriculture and herding slowly emerged from generations of observation and gentle guidance.

Part 2 - How These Changes Shaped People's Minds and Lives

This long transition from nomadic tribes to settled farmers shaped how people saw the world and themselves in big ways that still echo today. Let’s look closer at that.

First, as groups anchored to reliable water and rich lands for crops and grazing, deep ties to ancestral places formed over centuries. The meaning and memory soaked into the mudbrick houses, temple shrines, plowed fields, and pastoral ranges - this land they inhabited, nourished from and defended against drought or conflict. Cycles of seasons oriented ritual rhythms of life even as generations passed on.

Next, with granaries of grain and livestock pens came the concept of property ensuring bounty and plenty before others. Notions of terroir, irrigation rights, and migration routes emerged requiring protection and trade agreements with other tribes. Specialist craft roles developed in the villages and status distinctions arose.

Also, as wild plants and animals gradually became domesticated from among the abundance of regional life, the revered gifts of the earth's bounty were celebrated. But when harvests failed or herds sickened, propitiations to gods and spirits reflected a reliance on providence and luck, even as bone divination and observations of the heavens sought explanations.

Finally, bodily changes also unfolded across the centuries of settlement living. Skeletons came to average smaller statures with less strong joints from childhoods in plots and paddocks rather than ranging as foragers. Teeth show more decay and bone lesions from grit and infections. But skulls also enlarged to accommodate growing brains taxed with the management of acres and livestock rather than wide territories.

In summary, the transition mixed blessing and hardship, shaping identities and belief systems in the process. Narratives, rituals, and consummate skills arose and adapted to places that provided and periods that proved harsh. Lands, labors, and lives interwoven created legacies and limitations still subtly sensed even millennia later. But the wisdom to continue rebalancing skills, resources, and sharing as environments and neighbors change persists as their inheritance too.

Part 3 - How These Mindsets Lead to Conflicts

Now to understand how mindsets and views shaped so long ago lead to some of the conflicts still seen today in places like Israel, Palestine, Syria, or Iraq, we have to time travel forward thousands of years again...

By 6000 years ago, agriculture and herding fostered enough surplus crops, goods, and livestock to trade that cities arise. Many specialties converge - masons, merchants, priests, and governors direct laborers building temples and palaces. Scribes account for harvests and rations. Bronze metal workers equipped militias guarding caravans and buffer zones from nomadic herder clans disdained.

In such complex, hierarchical civilizations, origin narratives root identities. As dynasties vie over centuries, notions of sacred pacts to lands, divine favors, or even racial superiority become myths binding peoples across generations. Conquests and forced assimilations deepen grievances recalled. Rivers, mountains, and ruins become touchstones for irreconcilable claims even as descendants mingle.

Gradually tribesfolk fuse into cultural groups arrayed across the region - Canaanites, Phoenicians, Philistines, Hebrews, Amorites, or Moabites. By Roman and then Arabic expansions, destinies further diverge - Jewish diasporas await return to Jerusalem while Christians revere outposts. Muslim realms carry forward the pastoralist traditions, retaining migration routes. These identities harden against the backdrop of holy sites changing hands violently through the brutal crusades.

Colonialism leaves indelible partitions - Syria severed from Greater Syria (Bilad al-Sham), ethnicities dispersed across new borders by French and British bureaucrats. Stateless Kurds, Marsh Arabs, and Bedouin minorities lose pastoral ranges to national infrastructures like dams, pipelines, and settlements. Too often new rulers reinscribed lasting economic and social stratification.

So in essence, ancient agricultural transitions that enriched lifespan and technical innovation also opened differentiation from long interwoven threads of vital dwellers. What served survival split under the strain of ambitions. Lands long peopled became haunted by displaced visions that fossilized into algorithms of entitlement passed down unseen. Histories reduced to injustices fuel defensive rage and denials in repeating cycles.

Yet where heritage is honored in its complexity, hope persists! Covenants upholding rights and responsibility can root identities in shared humanity and destiny rather than divisions ordained from time immemorial. For continually this land has taught epics may inspire but wise adaptation, generosity, and care for those vulnerable matter most in the fullness of time. The future remains unwritten - if we allow records of relations to read and rewrite ourselves anew.

Samskaras and Vasanas

In Vedanta, vasanas are the subtle desires or tendencies that arise from the samskaras. They are the hidden marks in the mind that result from cravings, dislikes, and routines. Vasanas foster natural propensities and customary actions. Samskaras are the profound mental structures determined by previous deeds. They are the subconscious imprints that mold an individual’s character, originating from both this and past lives. Samskaras affect a person’s traits, outlooks, and possibilities.

In the heart of ancient eras, amid the dances of the stars, whispered a tale woven with subtle threads of human essence. Thirteen thousand years ago, in what we now call Israel, nomadic tribes were weavers of samskaras, the deep imprints of their lives, and vasanas, the impulses guiding their path.

Picture a young hunter, eyes gleaming with enthusiasm, chasing prey amidst the wild grasses. Every arrow shot and every fruit gathered shaped his samskara of prosperity and abundance. Yet, in the heart of the group, there were also those who, in times of scarcity, developed samskaras of fear, learning to face necessity with ingenuity.

We ascend in the tapestry of time by 3000 years, and the human landscape changes. Tribes settled in permanent villages and began to shape their destiny with mud houses and specialized tools. Here, a woman grinds wild grains into flour, creating samskaras of care and nourishment. In the cauldron of daily life, vasanas of community and interconnectedness are born.

Generations pass, and the village evolves into a community of 50-300 people, rooted in the land and the stars. Now, a blacksmith shapes vasanas of mastery in forging metal, while a basket weaver creates samskaras of beauty and utility. But in the quiet of the night, some minds nurture samskaras of jealousy, fueled by the shadow of competition.

The flow of time brings us to 9000 years ago, and the cultivated wheat fields now tell stories of samskaras of agricultural wisdom. Tribes learn to select the best animals for breeding, generating vasanas of discernment and prosperity. But over the years, the accumulation of property led to samskaras of attachment, challenging the wisdom of sharing from nomadic times.

Here, the transformation continues, with samskaras and vasanas interwoven in the stories of each individual. In smaller bodies and less robust joints, samskaras of adaptation to sedentary life emerge. Teeth show signs of decay, a result of samskaras of survival challenged by new hardships. But skulls expand, and with them grow samskaras of complex thinking and the management of territories.

Through the challenges and gifts of time, the transition shapes identities and beliefs. Narratives, rituals, and skills intertwine into a fresco that embraces challenging places and periods. Samskaras of resilience emerge in times of famine, while vasanas of gratitude unfold when the land yields its fruits.

And now, we transport ourselves to 6000 years ago, an era of cities and trade, of samskaras of prosperity and competition. But at the heart of these civilizations, samskaras of separation are born, of division between classes and status. The vasanas of ambition grow, fueled by stories of power and dominion.

Dynasties vie for the stage, and identities root themselves in samskaras of belonging to a sacred place or community. Wars, divine myths, and the force of conquests carve deep vasanas. Riverbanks and mountain peaks become touched by stories of triumphs and tragedies, shaping consciences with samskaras of glory and pain.

Then, in the whirlwind of colonization, samskaras of conquest and control insinuate themselves among nations. Lines drawn on maps by colonizers transform into vasanas of division and oppression. Nomadic tribes lose their lands, generating samskaras of loss and resistance, while new lords of the land impose themselves with samskaras of dominance and superiority.

The winds of change blow through the ages, and in the theater of colonial occupation, samskaras of struggle and resistance emerge. Landless people, displaced from their roots, bear the weight of samskaras of exile and disorientation on their shoulders. Vasanas of diaspora and the quest for identity weave among the fragments of history, while the lands themselves bear scars of samskaras of exploitation and degradation.

And thus, time brings us to the present day, where disputes inflame regions like Israel, Palestine, Syria, and Iraq. Ancient samskaras, etched into mental and physical landscapes, emerge like specters. Vasanas of belonging, protection, and vengeance intertwine in an intricate dance, fueling the flames of divisions.

However, in the heart of this intricate narrative, there is a call to the wisdom of Vedanta. Samskaras and vasanas, both positive and negative, are woven into the fabric of human existence. Stories of resilience, sharing, and understanding intertwine with those of conflict, division, and oppression. By recognizing these threads, we can discover the transformative power of awareness.

Imagine an elder who, despite the weight of samskaras of loss and pain, finds the strength to teach the youth the values of peace and unity. This is a samskara of wisdom that challenges the past. A mother, bearer of samskaras of exile, teaches her child the beauty of diversity, nurturing vasanas of understanding and acceptance.

Through awareness of these human stories, we can break the cycle of divisions. The practice of forgiveness becomes a powerful samskara, generating vasanas of reconciliation. Steps towards mutual understanding, sharing stories, and awareness of deeper connections create samskaras of peace and love.

The thread of human existence is a complex weave of samskaras and vasanas, woven into the tapestries of time. Awareness of this subtle fabric invites us to embrace the diversity of our stories, honor the scars of the past, and cultivate samskaras of compassion and healing. With a profound understanding of who we are and how we are connected, we can transform our collective story, embracing the eternal wisdom of Vedanta.

Source: "The Hilly Flanks and Beyond: Essays on the Prehistory of Southwestern Asia Presented to Robert J. Braidwood, November 15, 1982," edited by T. Cuyler Young, Jr., Philip E.L. Smith, and Peder Mortensen. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization No. 36. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Chicago, Illinois.

I have woven tales to share, for any who care to read them. My books await you on Google Books. Check also my stories on Medium.com.

I would be honoured if you considered subscribing to the Premium Contents of my Vedanta Substack and leaving feedback, comments, and suggestions both on this page and by writing to me at cosmicdancerpodcast@gmail.com.

Thank you for your precious attention.